The Uncertainty Principle (LOL):

Have you ever noticed how the best stories start with uncertainty? Like that moment when you’re watching a thriller and think you know who the culprit is, but you’re not quite sure. Your mind races through possibilities:

- “It’s definitely the butler” (75% confident)

- “Wait, maybe it’s the mysterious neighbor” (20% sure)

- “Plot twist: what if it’s the detective?” (5% wild guess)

Here’s the plot twist: this same dance of probabilities that makes mysteries exciting is exactly what makes machine learning powerful. Modern AI isn’t a know-it-all; it’s more like a seasoned detective weighing evidence.

Think about how revolutionary this is. We’ve moved from computers that could only understand “yes” or “no” to systems that can say:

confidence_level = {

"This is a cat": 0.93,

"This might be a very small dog": 0.06,

"Is that a weird-looking rabbit?": 0.01

}What makes this especially fascinating is how we can capture all this uncertainty in elegant mathematical equations. But before you run away screaming “Not math!”, let me promise you something:

Every equation we’ll look at is just putting numbers to things your brain already does intuitively so just STAY WITH ME!!

Throughout the article we’ll try to analyze some thoughts like:

- How to mathematically model “maybe”

- Why unexpected events carry more information

- How to measure the gap between what we think and what actually is

- How systems get better by embracing uncertainty

Ready to embrace the beauty of uncertainty? Let’s begin our investigation into the probabilistic nature of intelligence, both artificial and natural!

When Accuracy Isn’t Enough?

Let’s start with a real problem:

You’re a doctor who just received a new test for a rare disease. The test manufacturer says it’s “95% accurate”. A patient walks in, takes the test, and gets a positive result. What’s the probability they actually have the disease?

The Frequentist Approach

Most people would say “Easy! It’s 95%!” After all, that’s the test’s accuracy, right?

Let’s try the traditional frequency-based solution:

- Run the test on 1000 people

- Count how many positive results were correct

- Divide by total positive results

- That’s our probability!

But wait… there’s a catch. The disease is rare, affecting only 1 in 1000 people. Now our frequency calculations get interesting:

- In 1000 people, only 1 person actually has the disease

- With 95% accuracy, the test will correctly identify this 1 person

- But it will also incorrectly flag about 50 healthy people (5% of 999)

- So out of 51 positive results, only 1 is correct!

The actual probability is closer to 2%, not 95%. Mind blown yet?

When Frequencies Fail

But here’s the real problem - we can’t actually run this experiment 1000 times for our current patient. We have:

- One patient

- One test result

- One decision to make

We need a way to reason about this specific case, using everything we know.

Enter Bayesian Thinking

This is where Bayesian probability shines. Instead of counting frequencies, we think about:

- What we knew before the test (prior)

- What the test tells us (evidence)

- How to combine these (update)

For our patient:

- Prior: 1/1000 chance of disease (population rate)

- Evidence: Positive test result (95% accurate)

- Update: Combine these mathematically (we’ll show how!)

The Bayesian Formula

This thinking gives us the famous Bayes’ Theorem: \[ P(Disease|Positive) = \frac{P(Positive|Disease) \times P(Disease)}{P(Positive)} \]

Where:

- \(P(Disease|Positive)\) is what we want: probability of disease given a positive test

- \(P(Positive|Disease)\) is 0.95 (test sensitivity)

- \(P(Disease)\) is 1/1000 (disease prevalence)

- \(P(Positive)\) needs to be calculated using total probability

To find \(P(Positive)\), we consider both ways to get a positive result:

- Having the disease and testing positive

- Not having the disease but testing positive anyway

Mathematically: \(P(Positive) = P(Positive|Disease)P(Disease) + P(Positive|No Disease)P(No Disease)\)

Plugging in our numbers: \(P(Positive) = 0.95 \times (1/1000) + 0.05 \times (999/1000)\) = 0.0509

Now we can solve our original equation:

\[ P(Disease|Positive) = \frac{0.95 \times (1/1000)}{0.0509} \approx 0.019 \]

That’s about 2%! Even with a “95% accurate” test, a positive result only means a 2% chance of actually having the disease. This surprising result comes from combining three pieces of information:

- How rare the disease is (prior probability)

- How accurate the test is (sensitivity)

- How often it gives false alarms (specificity)

Modern ML models work in a similar way. When a model says “I’m 90% confident this is a cat’s image”, it’s not just matching pixels - it’s combining prior knowledge about what cats look like with the specific evidence in the image. Just like our medical test, it’s all about updating beliefs with evidence!

Entropy: How Surprising is a Surprise?

Remember our medical test that was “95% accurate” but only gave us 2% certainty? This raises an interesting question: How much did that test result actually tell us?

Sure, we went from 0.1% (prior probability) to 2% (posterior probability) - but how do we measure how much information we actually gained? If another test took us from 2% to 40%, which update was more significant?

Think about surprise in your daily life:

- If I tell you the sun will rise tomorrow, that’s 0% surprising

- If I tell you it will snow in the Sahara today, that’s extremely surprising

- If I tell you a fair coin landed heads, that’s somewhere in between

This gets to the heart of information theory - the more surprising an event is, the more information it contains. When something completely expected happens, we learn nothing new. When something unexpected happens, we learn a lot.

Let’s make this concrete. In the first chapter, you might think:

- The butler did it (50%)

- The maid did it (30%)

- The gardener did it (20%)

When you learn it wasn’t the butler, how much does this tell you? This revelation forces a big update in your beliefs. But if you learn it wasn’t the gardener? That’s less informative - you already thought they were unlikely.

But how do we actually measure surprise? Let’s think about what properties our measure should have:

First, surprise must be a function of probability - the likelihood of an event should determine how surprising it is. Let’s call this function f(p).

What properties should \(f(p)\) satisfy?

- When we’re certain \((p = 1)\), we should have zero surprise: \(f(1) = 0\)

- As events become less likely \((p → 0)\), our surprise should increase: \(f(p)\) should increase as \(p\) decreases

- When two independent events occur together, their surprises should add: \(f(p₁p₂) = f(p₁) + f(p₂)\)

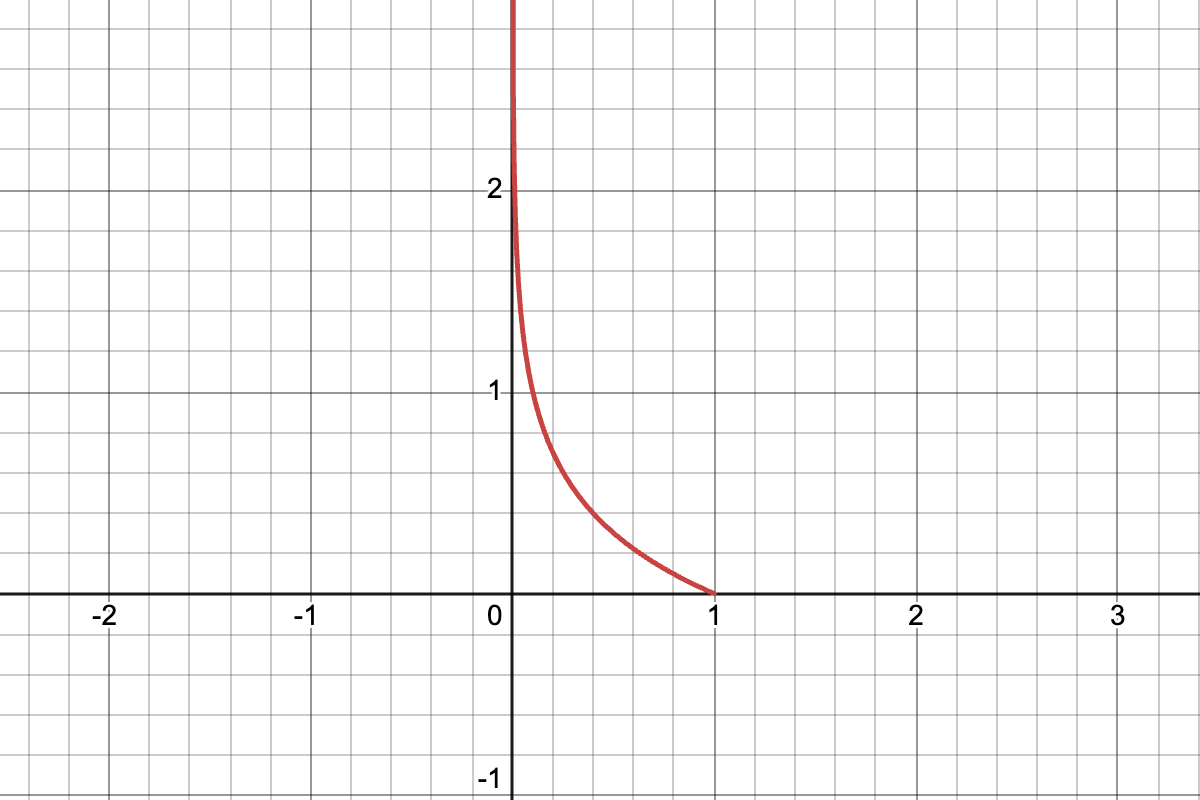

The logarithm emerges as the perfect candidate! It’s the only simple function that satisfies all these properties:

\[ \text{surprise}(p) = -\log(p) \]

Look how beautifully it works:

- \(log(1) = 0\), so certain events have zero surprise

- As p gets smaller, \(-log(p)\) grows larger

- \(log(p₁p₂) = log(p₁) + log(p₂)\), so surprises add up

Now that we have our measure of surprise \((-log(p))\), let’s think about entire probability distributions, not just single events. In our mystery novel, at any point we have:

- A list of suspects

- Each with their own probability

- Each probability would give us some surprise if that person turned out to be guilty

What if we want to measure how “uncertain” this whole situation is? We can:

- Calculate how surprising each outcome would be \((-log(p))\)

- Weight each surprise by how likely it is to happen (multiply by p)

- Add them all up

OR in simple language, just take the average, this gives us Entropy:

\[ H(P) = -\sum_i p_i \log(p_i) \]

The higher the entropy:

- The more spread out our probabilities are

- The more uncertain we are about what will happen

- The more information we’ll gain when we learn the truth

This idea is central to machine learning. When a model says “80% sure this is a cat”, it’s not just picking the most likely answer - it’s navigating a landscape of possibilities, each with its own probability and potential for surprise.

Cross-Entropy: When Reality Doesn’t Match Our Beliefs

From measuring “how uncertain we are” (entropy), we can pose a natural question about “how wrong we are”.

In our mystery novel example:

- You have your theory about who did it (your probability distribution)

- Your friend has a different theory (their distribution)

- The author knows the truth (the real distribution)

Or back to our medical test:

- The test manufacturer claims 95% accuracy (their distribution)

- The reality turned out quite different (true distribution)

How do we measure this mismatch? This brings us to cross-entropy - a measure of how surprised we’d be if we believed in one distribution but reality followed another.

Let’s make this concrete using our mystery novel. Suppose:

| Suspect | Truth (Author) (P) | Your Belief (Q) |

|---|---|---|

| Maid | 100% | 30% |

| Butler | 0% | 60% |

| Gardener | 0% | 10% |

Cross-entropy measures your surprise when reality (P) reveals itself, but you’ve been working with your beliefs (Q). Mathematically:

\[ H(P,Q) = -\sum_i p_i \log(q_i) \]

The larger this value, the more your beliefs diverged from reality. In essence, it measures how well your probability distribution matches the true distribution.

As a fun exercise, I encourage you to think about why we place \(q_i\) inside the logarithm and use \(p_i\) as the weight. Reflect on this question, and feel free to share your thoughts with me on my socials—I’d love to read your responses! 😄

This is why cross-entropy is everywhere in machine learning:

- P represents the true labels (“it really is a cat”)

- Q represents the model’s predictions (“I think it’s 80% cat, 20% dog”)

- Training aims to make Q match P as closely as possible

KL-Divergence: How Wrong Is Wrong?

We’ve seen how cross-entropy measures our total surprise when reality doesn’t match our beliefs. But here’s an interesting question: isn’t some of that surprise just… inevitable? Even if we knew the true probabilities, wouldn’t we still have some uncertainty?

Let’s say we’re analyzing student performance in an exam:

| Grade | True Distribution (P) | Your Model’s Prediction (Q) |

|---|---|---|

| A | 30% | 60% |

| B | 45% | 25% |

| C | 25% | 15% |

Even if you knew the true distribution:

- You still can’t predict exactly what grade each student will get

- There’s inherent uncertainty in the system

- This base uncertainty is measured by entropy of \(P\)

But with your model’s predictions:

- You’re not just facing the inherent uncertainty

- You’re also dealing with being wrong about the probabilities

This extra uncertainty is what KL divergence measures. Think about it:

- \(H(P,Q)\) is your total surprise using wrong beliefs

- \(H(P)\) is the surprise you’d have with perfect knowledge

- Subtracting \(H(P)\) from \(H(P,Q)\) leaves just the extra surprise from being wrong!

So we can write it down mathematically as: \[ D_{KL}(P||Q) = H(P,Q) - H(P) \]

Or written another way: \[ D_{KL}(P||Q) = \sum_i p_i \log(\frac{p_i}{q_i}) \]

Think of KL divergence as the “price of ignorance” - how much extra uncertainty we face because our beliefs don’t match reality. It’s like nature saying “Here’s your penalty for being wrong!”

This is why KL divergence is so important in machine learning. When we train models, we want to minimize this extra surprise - the part that comes from our model being wrong, not from the inherent uncertainty in the problem.

The Final Piece: Making Likely Stories

So we started by questioning probabilities? And then dove deep into measuring surprise, uncertainty, and even how wrong our beliefs can be? Well, there’s one more perspective that ties everything together beautifully.

Let’s flip our thinking:

Instead of asking “how surprised are we when reality differs from our beliefs?”, let’s ask “how likely was reality according to our beliefs?”

Think about our student grades example:

| Grade | True Distribution (P) | Your Model’s Prediction (Q) |

|---|---|---|

| A | 30% | 60% |

| B | 45% | 25% |

| C | 25% | 15% |

Now imagine we observe 3 students getting grades: B, A, B According to your model, the likelihood of seeing this sequence is:

\[ P(BAB) = 0.60 × 0.25 × 0.25 = 0.0375 \]

But according to the true distribution: \[ P(BAB) = 0.30 × 0.45 × 0.45 = 0.06075 \]

The true distribution made these observations more “likely” than your model did. This suggests your model isn’t great - but we already knew that!

The interesting part? When we work with logarithms of these likelihoods: \[ \text{Log Likelihood} = \log(P(BAB)) = \log(P(B)) + \log(P(A)) + \log(P(B)) \]

Notice something familiar? These are exactly our surprise values from before, just with a different sign! \[ \text{Less surprise} = \text{higher likelihood} \]

This gives us another way to think about training models:

- Instead of minimizing surprise (cross-entropy)

- We can maximize likelihood

- They’re two sides of the same coin!

Mathematically, for a model with parameters θ, maximizing likelihood means:

\[ \theta^* = \arg\max_\theta \prod_{i=1}^n P(x_i|\theta) \]

But because logs are monotonic (and easier to work with), we usually maximize log likelihood:

\[ \theta^* = \arg\max_\theta \sum_{i=1}^n \log P(x_i|\theta) \]

And here’s the beautiful part - maximizing log likelihood is equivalent to minimizing KL divergence between our model and reality!

Wait… WHY? Let’s connect the dots:

- Remember KL divergence? \(D_{KL}(P||Q) = H(P,Q) - H(P)\)

- That \(H(P)\) term? It’s the entropy of the true distribution - a constant we can’t control!

- So minimizing KL divergence is the same as minimizing cross-entropy \(H(P,Q)\)

- And cross-entropy is just our average surprise using the wrong distribution: \(H(P,Q) = - \sum_i p_i \log(q_i)\)

- Flip the sign, and what do you get? Log likelihood!

We’ve come full circle:

- Entropy measures uncertainty

- Cross-entropy measures total surprise

- KL divergence measures extra surprise

- And likelihood ties it all together!

So next time someone asks why we use log likelihood in machine learning, you can tell them: “Because surprise and likelihood are just two ways of looking at the same thing!”

Conclusion

We started by questioning simple probabilities and ended up discovering how machines learn from their mistakes. From counting to beliefs, from surprise to uncertainty, from measuring our mistakes to finding the most likely truth - every piece connected beautifully to reveal the deeper patterns in how we learn from data.

Next time you see terms like “cross-entropy loss” or “maximum likelihood” in machine learning, you’ll know there’s a deeper story - one about beliefs, surprises and lots of uncertainty 😄

Want more intuitive explanations like these? Find me on:

- X: @swayaminsync

- LinkedIn: /in/swayam-singh-406610213

- Website: https://swayaminsync.github.io/